Spartacus was a gladiator and a slave who led a rebellion against the Roman Republic. He was born in Thrace and sold into slavery, eventually becoming a gladiator in the city of Capua. In 73 BC, he and a group of other gladiators escaped and began a rebellion against the Roman Republic. They were able to defeat several Roman armies before being ultimately defeated by Marcus Licinius Crassus. Spartacus died in 71 BC, and his body was never found. His rebellion inspired other slave revolts throughout history.The Greek essayist Plutarch describes Spartacus as "a Thracian of Nomadic stock",[5] in a possible reference to the Maedi tribe.[6] Appian says he was "a Thracian by birth, who had once served as a soldier with the Romans, but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator".[7]

Florus described him as one "who, from a Thracian mercenary, had become a Roman soldier, that had deserted and became enslaved, and afterward, from consideration of his strength, a gladiator".[8] The authors refer to the Thracian tribe of the Maedi,[9][10][11] which occupied the area on the southwestern fringes of Thrace, along its border with the Roman province of Macedonia – present day south-western Bulgaria.[12] Plutarch also writes that Spartacus's wife, a prophetess of the Maedi tribe, was enslaved with him.

The name Spartacus is otherwise manifested in the Black Sea region. Five out of twenty Kings of the Thracian Spartocid dynasty of the Cimmerian Bosporus[13] and Pontus[14] are known to have borne it, and a Thracian "Sparta" "Spardacus"[15] or "Sparadokos",[16] father of Seuthes I of the Odrysae, is also known.

One modern author estimates that Spartacus was c. 30 years old at the time he started his revolt,[17] which would put his birth year c. 103 BC.

The response of the Romans was hampered by the absence of the Roman legions, which were engaged in fighting a revolt in Hispania and the Third Mithridatic War. Furthermore, the Romans considered the rebellion more of a policing matter than a war. Rome dispatched militia under the command of the praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber, who besieged Spartacus and his camp on Mount Vesuvius, hoping that starvation would force Spartacus to surrender. They were taken by surprise when Spartacus used ropes made from vines to climb down the steep side of the volcano with his men and attacked the unfortified Roman camp in the rear, killing most of the militia.[24]

The rebels also defeated a second expedition against them, nearly capturing the praetor commander, killing his lieutenants, and seizing the military equipment.[25] Due to these successes, more and more slaves flocked to the Spartacan forces, as did many of the herdsmen and shepherds of the region, swelling their ranks to some 70,000.[26] At its height, Spartacus's army included many different peoples, including Celts, Gauls, and others. Due to the previous Social War (91–87 BC), some of Spartacus's ranks were legion veterans.[27] Of the slaves that joined Spartacus ranks, many were from the countryside. Rural slaves lived a life that better prepared them to fight in Spartacus's army. In contrast, urban slaves were more used to city life and were considered "privileged" and "lazy."[28]

In these altercations, Spartacus proved to be an excellent tactician, suggesting that he may have had previous military experience. Though the rebels lacked military training, they displayed skilful use of available local materials and unusual tactics against the disciplined Roman armies.[29] They spent the winter of 73–72 BC training, arming and equipping their new recruits, and expanding their raiding territory to include the towns of Nola, Nuceria, Thurii, and Metapontum.[30] The distance between these locations and the subsequent events indicate that the slaves operated in two groups commanded by Spartacus and Crixus.[citation needed]

In the spring of 72 BC, the rebels left their winter encampments and began to move northward. At the same time, the Roman Senate, alarmed by the defeat of the praetorian forces, dispatched a pair of consular legions under the command of Lucius Gellius and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus.[31] The two legions were initially successful—defeating a group of 30,000 rebels commanded by Crixus near Mount Garganus[32]—but then were defeated by Spartacus. These defeats are depicted in divergent ways by the two most comprehensive (extant) histories of the war by Appian and Plutarch.[33][34][35][36]

Alarmed at the continued threat posed by the slaves, the Senate charged Marcus Licinius Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome and the only volunteer for the position,[37] with ending the rebellion. Crassus was put in charge of eight legions, numbering upwards of 40,000 trained Roman soldiers;[37][38] he treated these with harsh discipline, reviving the punishment of "decimation", in which one-tenth of his men were slain to make them more afraid of him than their enemy.[37] When Spartacus and his followers, who for unclear reasons had retreated to the south of Italy, moved northward again in early 71 BC, Crassus deployed six of his legions on the borders of the region and detached his legate Mummius with two legions to maneuver behind Spartacus. Though ordered not to engage the rebels, Mummius attacked at a seemingly opportune moment but was routed.[39] After this, Crassus's legions were victorious in several engagements, forcing Spartacus farther south through Lucania as Crassus gained the upper hand. By the end of 71 BC, Spartacus was encamped in Rhegium (Reggio Calabria), near the Strait of Messina.

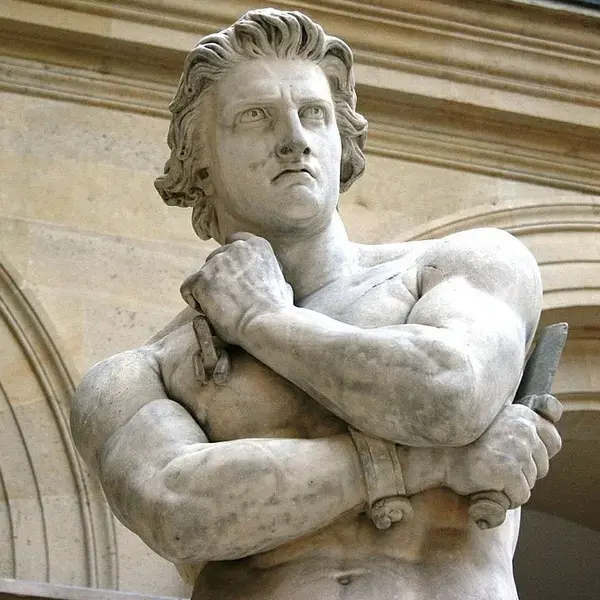

A 19th-century depiction of the fall of Spartacus by the Italian Nicola Sanesi (1818–1889)

According to Plutarch, Spartacus made a bargain with Cilician pirates to transport him and some 2,000 of his men to Sicily, where he intended to incite a slave revolt and gather reinforcements. However, he was betrayed by the pirates, who took payment and then abandoned the rebels.[39] Minor sources mention that there were some attempts at raft and shipbuilding by the rebels as a means to escape, but that Crassus took unspecified measures to ensure the rebels could not cross to Sicily, and their efforts were abandoned.[40] Spartacus's forces then retreated toward Rhegium. Crassus's legions followed and upon arrival built fortifications across the isthmus at Rhegium,[citation needed] despite harassing raids from the rebels. The rebels were now under siege and cut off from their supplies.[41]

At this time, the legions of Pompey returned from Hispania and were ordered by the Senate to head south to aid Crassus.[42] Crassus feared that Pompey's involvement would deprive him of credit for defeating Spartacus himself. Hearing of Pompey's involvement, Spartacus tried to make a truce with Crassus.[43] When Crassus refused, Spartacus and his army broke through the Roman fortifications and headed to Brundusium with Crassus's legions in pursuit.[44]

When the legions managed to catch a portion of the rebels separated from the main army,[45] discipline among Spartacus's forces broke down as small groups independently attacked the oncoming legions.[46] Spartacus now turned his forces around and brought his entire strength to bear on the legions in a last stand, in which the rebels were routed completely, with the vast majority of them being killed on the battlefield.[47]

The final battle that saw the assumed defeat of Spartacus in 71 BC took place on the present territory of Senerchia on the right bank of the river Sele in the area that includes the border with Oliveto Citra up to those of Calabritto, near the village of Quaglietta, in the High Sele Valley, which at that time was part of Lucania. In this area, since 1899, there have been finds of armour and swords of the Roman era.

Plutarch, Appian, and Florus all claim that Spartacus died during the battle, but Appian also reports that his body was never found.[48] Six thousand survivors of the revolt captured by the legions of Crassus were crucified, lining the Appian Way from Rome to Capua, a distance of more than 100 miles.