Personal

Other names:

Baron de l'Aulne

Baron de l'Aulne

Job / Known for:

Comptroller general of finance under Louis XVI

Left traces:

Reforms in taxation, trade, agriculture

Born

Date:

1727-05-10

Location:

FR

Paris, France

Died

Date:

1781-03-18 (aged 54)

Resting place:

FR

Death Cause:

Gout

Family

Spouse:

Children:

Parent(s):

Michel-Étienne Turgot and Madeleine Francoise Martineau de Brétignolles

QR Code:

My QR code:

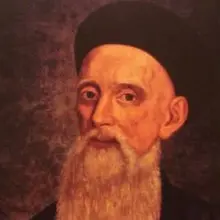

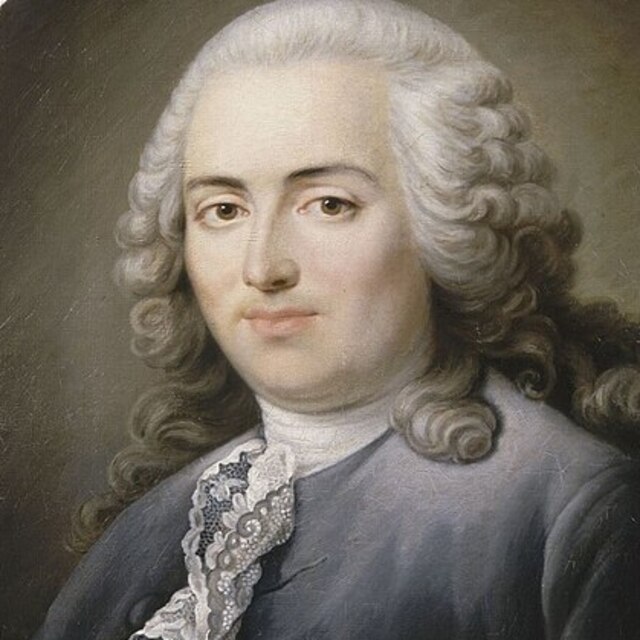

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

https://DearGone.com/10502

My QR code:

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

https://DearGone.com/10502

Key Ownner:

Not yet supported by key owner

Show More

Rank

Users ranking to :

Thanks, you rate star

Ranking

5.0

1

Fullname

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Fullname NoEnglish

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Slogan

No one loves the bearer of bad news.

About me / Bio:

Show More

Article for Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Died profile like Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Comments: